Complementary Distribution

Most textbooks are dull and boring. I don’t know if they start out that way or if a committee surgically removes all traces of an author’s voice. Suffice it to say, a good textbook is usually the first line of defense against insomnia.

Point in case: my Contemporary Linguistics textbook for English 304. Not only is it filled with strange symbols and phonetic transcriptions, the likes of which I hadn’t seen prior to writing Spanish papers, but the terminology is so far removed from my vernacular that looking at it gives me a headache.

About a week ago, I was slogging through a particularly confusing section on complementary distribution. After three paragraphs into the reading, I had no idea what the term meant. The text seemed upbeat in its description, yet the phonemes in the example appeared to have exclusive properties. If you’re feeling lost, don’t worry―I’m doing this to illustrate a point.

Then, in the following paragraph, the text became crystal clear. “Wow,” I thought, “why didn’t they just say that in the first place?” Reading the final sentence in the fourth paragraph, I did a double-take. “No way! Did I read that correctly?”

I read it again and again. Just to be sure, I read it a third time. Then I burst out laughing. If only every textbook contained these kinds of Easter eggs! Honestly, students would stick to the pages like glue.

Here’s the passage:

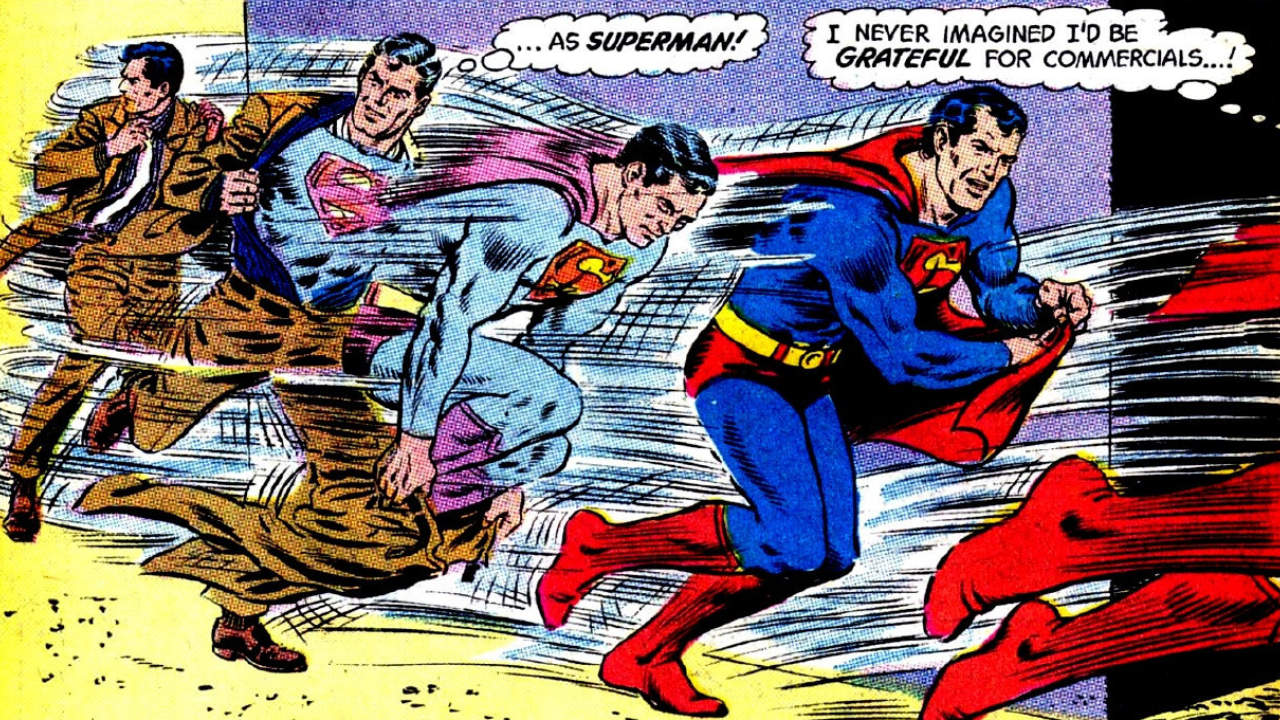

Since no voiced [l] ever occurs in the same phonetic environment as a voiceless one (and vice versa), we say that the two variants of l are in complementary distribution. Complementary distribution means that the two sounds never occur in the same place (like Clark Kent and Superman).

Contemporary Linguistics